Book Review: ARTIST-TEACHER: A PHILOSOPHY FOR CREATING AND TEACHING (2010)

ARTIST-TEACHER: A PHILOSOPHY FOR CREATING AND TEACHING

Author: G. James Daichendt

Publisher: Intellect Books, 2010

In his book, Artist-Teacher: a philosophy for creating and teaching (2010), G. James Daichendt explores the dichotomous nature of the artist-teacher concept and major movements that sprouted in art education history to better understand it. Divided into two sections, the book opens with Part One: Teaching Artist or Artist-Teacher? wherein the reader is introduced to the author’s nuanced historical undertaking. Part Two: Artist-Teachers, deepens the reader’s understanding with specific historical sketches of key educators who were also practicing artists, such as George Wallis, Arthur Wesley Dow, and Walter Gropius of the Bauhaus among others. The author’s professional background includes serving as Associate Dean and Professor of Art at Azusa Pacific University, and adjunct professor at Boston University’s M.A. in Art Education program.

Part One of Artist-Teacher contains three chapters that help to introduce the book’s purpose. Chapter One: The Evolution of Teaching Art, starts by setting the stage with a question: Why do we teach art? Here, we learn about the multiple roadmaps available to becoming an art educator considering the various types of credentialing institutions. From the fine art student with an MFA to the school teacher, the range of art education positions and the preparation to have them are not uniform. Daichendt contends that there exists no single “right way” to teach or learn visual arts and that the absence of a single unifying philosophy is the philosophy of art education today (p. 5), like the line of best fit on a graph with multiple data points. Chapter Two: The Artist-Teacher: From the Classical Era to the 21st Century, sheds light on the past, chronologically, to understand the present discourse surrounding the term’s application and how it came to be. The fact that painters and craftsmen of Classical Greece were seen more as manual workers than intellectual creators, as many are seen now, helps us appreciate the evolution of this creative field. The chapter covers a rich history of art and how it was taught in the Middle Ages, The Renaissance, the French Academy, and how England’s Normal School of Design came to be. In sum, the strict rules which governed much of the European academies were gone by the time the Normal School was established in late-19th Century Boston. Marking the end of the apprenticeship-style model of education, educators with no art background could now teach art in the school system, and this alone was a radical idea (Efland 1990, p. 108, as cited in Daichendt, 2010, p. 52).

While the first two chapters provide a necessary panoramic view of art education history, it is Chapter Three, The Artist-Teacher: Just Another Title or a Distinctive Notion? that delves deeply into the philosophical heart of the book. Here, Daichendt explains the first time he encountered the term artist-teacher, recounting how certain people in a school of education used the term to describe themselves and “their commitment to art production and teaching” (p. 63). It was this spark that led to his nascent inquiry to ask further questions on the history of the term itself if there was such a thing. The chapter does an excellent job at discussing how a scholarly debate erupted in 1959, one in favor of the term artist-teacher and the other condemning it. In essence, the book serves in defense of the counterpoint provided by Willard McCracken, who argued that the “artist-teacher was a concept and evolutionary change rather a descriptive term” (p. 64).

The argument that ensues is that art teachers should be knowledgeable in the production and artistic thinking that makes it essential for the student’s classroom experience. The term itself does not demand that art teachers show in galleries or maintain the prototypical artist’s lifestyle. Instead, its goal is to re-assert the expertise required of art-making. The sheer controversy behind the term allows Daichendt to clarify for the reader that the artist-teacher can be seen as a philosophy for teaching, and more importantly, acknowledges that “there are two distinct fields coming together in the term”, art and education, which can make it problematic for many already in the field (p. 61). Contrary to what critics of the term have to say, the author maintains that “The individual determines success” (p. 64), which gives an optimistic and flexible point of view for anyone interested in becoming an art educator.

(Daichendt, 2010, pg. 108)

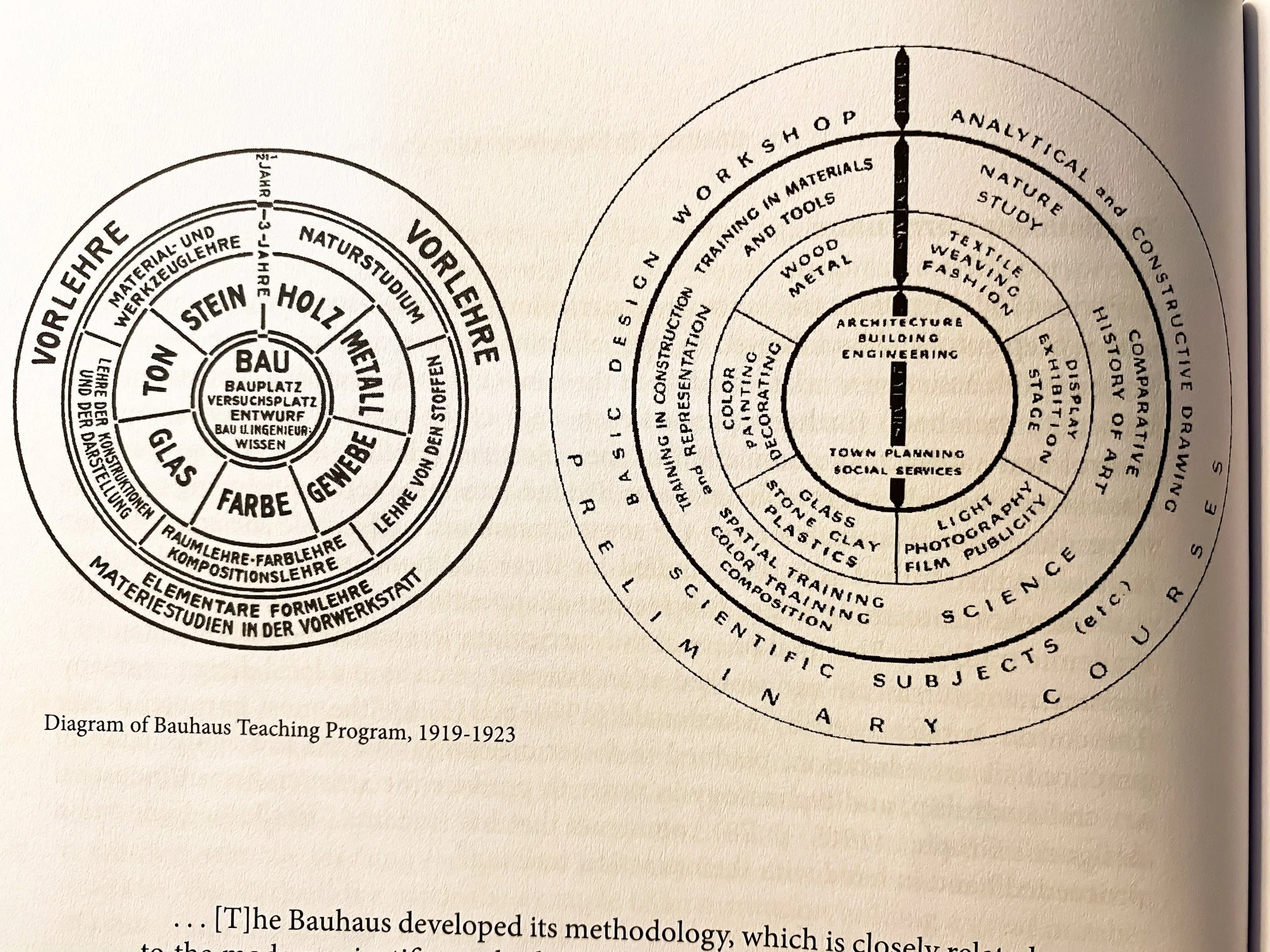

The second half of the book focuses on specific biographical historical studies of prominent educators and ends with a reflection in Chapter Nine: Redefining the Artist-Teacher. Beginning with Chapter Four: The Original Artist-Teacher, on the unique set of circumstances which George Wallis faced (1811–1891) the contemporary art education student can glean how past educators created new avenues for teaching in their time. The work and legacy of Arthur Wesley Dow (1857–1922) is the focus of Chapter Five: A Systematic Grammar. Chapter Six: Bauhaus to Black Mountain is especially revelatory. The author cites a researcher who deemed the Bauhaus pedagogy as too “richly faceted” and varied for the Bauhaus to define itself under a single philosophical platform (p. 106). This observation ties in almost to the letter with Daichendt’s perspective that there are multiple philosophies espoused simultaneously by various educators, which he restates in this section.

As a disclaimer, I should state that I am a graduate student in art education at Boston University’s online program. I found the book to be rather illuminating and the argument for the artist-teacher philosophy compelling in its approach. It provides a structure where the field of art education needs it most. Under 200 pages, it is concise but rich, and it gives the reader plenty of sources at the end of each chapter to pursue further study. I also found it adequate for both undergraduate and graduate levels, and anyone interested in an introduction to the history of art education. To learn about past artist-teachers and the lives they carved out for themselves to satisfy their visual art practice was especially useful as many of the pedagogical methods they employed paralleled an active artmaking life. Navigating both fields, of artist and educator, was most likely not an easy task for any of those profiled, as the author describes the 19th Century Artist-Teacher examples of Wallis and Dyce (p. 81).

The book concerns itself with exploring the pedagogical evolution of art in the West. The author cites several primary sources, ranging from Johannes Itten’s preliminary course details (p. 111) to examples of Arthur Wesley Dow’s students’ works (p. 97). The value given to primary sources in a historical study is paramount to the researcher. It becomes clear, as the author reiterates in his closing chapter, that his concern for art education programs at the college level today is rooted in the observation that emphasis on the artistic process has been bypassed almost entirely (pp. 148 -149). Whether knowingly or not, “the role of the artist has been raised and smothered because of the complications the two roles hold for one-another” (p.149).

Ultimately, Daichendt makes an impassioned call to arms for the pedagogy of art to balance itself. I share this view wholeheartedly but admit that it has been over ten years since its publishing. The argument is a logical one. One can relegate the author’s argument for a more artist-centered stance in teaching to that of a historian’s reliance on primary sources. If too removed from the primary source (the artist) the historian will most likely produce subpar research (the teaching). Looking ahead now since Artist-Teacher was published, I wonder if the author will add to or revise his philosophy. It appears that the art education field is still somewhat unregulated, where the internet is no doubt playing a major role in shaping the next generation of educators. Yet, it helps to have sources of inquiry, such as this book, that give future art educators something to think about as they enter the field more informed of the traditions and potential setbacks that they may face.

References

Daichendt, G. J. (2010). Artist-teacher: a philosophy for creating and teaching. The University of Chicago Press.

This story was not commissioned by any of the entities mentioned. If you would like to support my work, please consider subscribing to Medium using my membership link, and you’ll have access to all content by Medium creators. Thank you. https://medium.com/@claudiavillalta/membership